Svelte reactivity — an inside and out guide

I've been working with svelte exclusively for a year now, but I still manage to shoot myself in the foot every now and then when using reactive state. Some of the confusion is due to my prior experience with React, but some points are confusing on their own. Today, I dive into svelte internals to understand what's really going on.

- When you mutate svelte object state, do you really mutate the JS object?

- Why doesn't

array.pushtrigger an update? - How are $-dependencies determined?

- Does setting a variable to its current value trigger an update?

- Does a block using one object field,

state.field, only run on changes to this field? - Why do $-variables behave a bit weirdly under JS scoping rules?

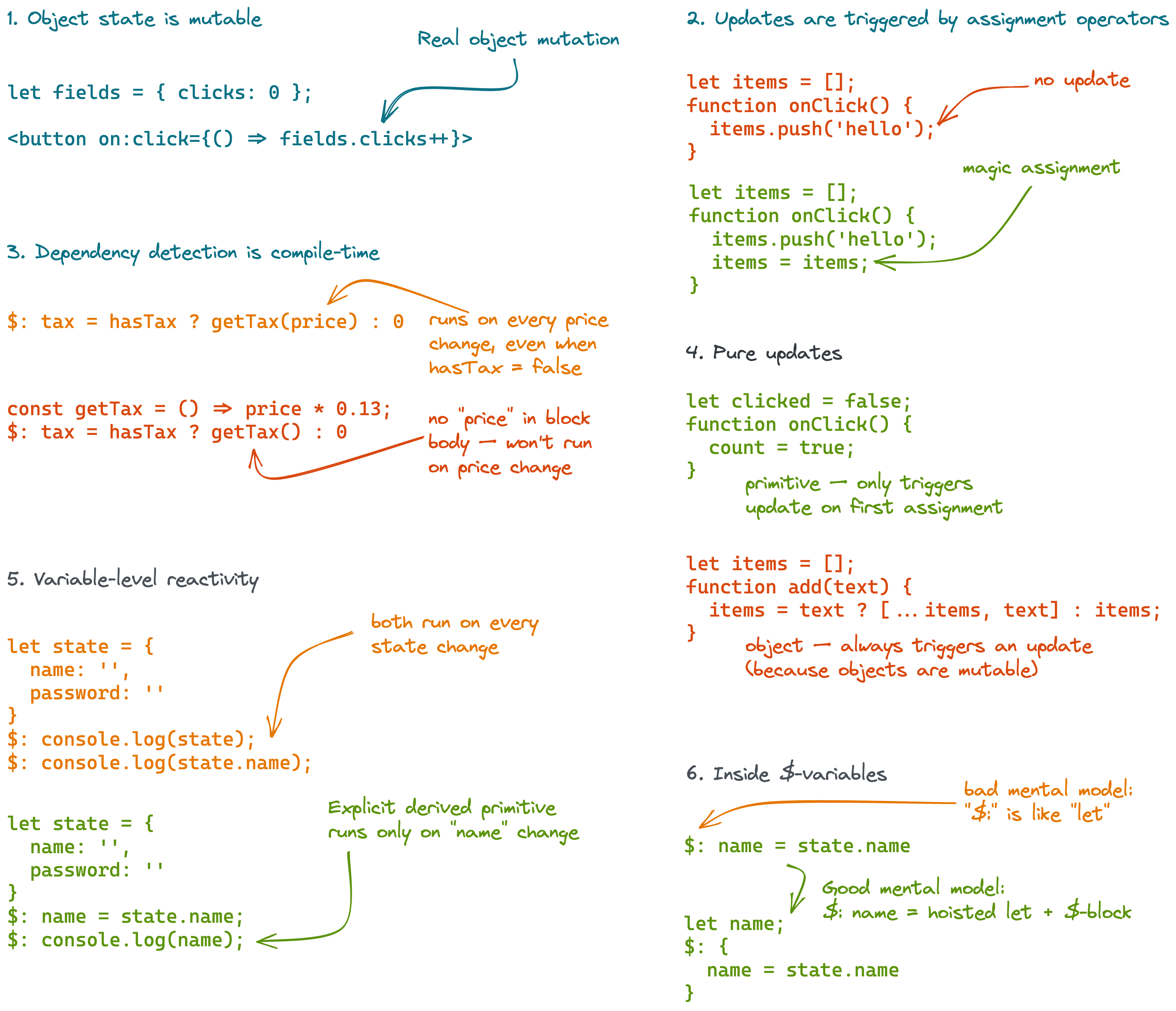

We won't talk about stores too much, we still have a lot to discuss before we get there. If you're in a hurry, here's a customary cheat-sheet:

Let's go!

Object state is mutable

One thing that caught me off guard, coming from react, is that object state is mutable — the exact object defined as the initial value will stay there as long as you don't reassign the variable:

// data is always the same object

let data = {

active: 0

};

const toggle = () => data.active = !data.active;

<button on:click={toggle}>

{data.active ? 'on' : 'off'}

</button>See repl. By the way, this behavior also applies to stores. This is in contrast to react, where most optimizations rely on "purity" — a thing is only considered changed if its reference changes.

So, svelte state is not an observable object built by JS means, but a regular JS variable with an update event bus attached separately. So far so good — the svelte way is close to how JS works. But what actually triggers the update event?

Updates are triggered by assignment operator

The big selling point of svelte is its concise syntax. As a showcase example, you often see what looks like simple JS, but changing the variable magically updates the component:

let isOn = 0;

<button on:click={() => isOn = !isOn}>

{isOn ? 'on' : 'off'}

</button>The magic disappears once you get to mutable objects — calling array.push() or any other mutating method does not trigger an update:

let items = [];

function addItem(text) {

items.push(text);

}

{items.join(' ')}

<button on:click={() => addItem('hehe')}>

more!

</button>This seems very familiar to react developers — of course, mutating the object does not change its reference, so further updates are skipped! To add to the confusion, react-style immutable update like items = [...items, text] fixes the problem. However, svelte state is mutable, and the real issue is the lack of an assignment operator which actually triggers the update, so the weird self-assignment pattern works just as well:

let items = [];

function addItem(text) {

items.push(text);

// #enable_magic

items = items;

}Any flavor of assignment operator (+=, ++, and so on) works, but it must be present for the update to happen. Another thing to note is that update logic is dynamic, not a strict "if callback X runs, fire listeners to variable Y" rule. The assignments are compiled to a call like $$invalidate(0, items), so conditional assignment only triggers updates if it's executed:

// only triggers an update if text is truthy

function addItem(text) {

if (text) {

items = [...items, text];

}

}

// always triggers an update

function addItemAlways(text) {

items = text ? [...items, text] : items;

}Dependencies are determined statically

Unlike invalidation, which happens dynamically at runtime, $-blocks dependencies are determined statically at compile-time. If you have some logic that only depends on text if isTracking is true...

let isTracking = false;

let text = '';

$: if (isTracking) {

console.log(text);

}...the block runs on every text change regardless of isTracking value, because both referenced variables, text and isTracking, are recognized as the block dependencies. This is in contrast to runtime reactivity, as seen in MobX — there's no way to even see the dependency on text if the code accessing it does not run.

One inconvenient side-effect of this dependency detection mechanism is the lack of visibility into implicit function dependencies. Say you have this code:

let items = ['hello', '', 'friend'];

const getNonempty = () => items.filter(x => !!x);

$: nonempty = getNonempty();Since the $-expression defining nonempty does not explicitly mention items, it will not run on items change. Fix: avoid functions in $-blocks, or make sure they're pure (only depend on their arguments), or (worst case) make the function itself derived: $: getNonempty = ...

Primitive updates are pure

Based on the points above, you'd assume that assigning to the variable always triggers an update, but that's not the case. When repeatedly setting a variable to true, only the first change results in an update:

let isEnabled = false;

// only run on the first click

afterUpdate(() => console.log('updated'));

$: console.log({ isEnabled });

<button on:click={() => isEnabled = true}>

{isEnabled ? 'clicked' : 'click me'}

</button>In general, setting a primitive variable to its current value does not trigger an update. Here's the svelte code that implements this optimization.

Object updates are not pure

But in that case, how on earth can this support object mutation and self-assignment that don't change the object reference? Well, the trick is simple — it doesn't. Wrapping isEnabled with an object removes the optimization, and now the update happens on every click:

let state = { isEnabled: false };

// runs on every click

afterUpdate(() => console.log('updated'));

$: console.log(state.isEnabled)

<button on:click={() => state.isEnabled = true}>

{state.isEnabled ? 'clicked' : 'click me'}

</button>The code implementing the comparison always says "it's changed" when it sees an object.

Reactivity is variable-grained

As we've just seen, object state is always treated as a whole — there is no field-level reactivity. If you have an $-block that only depends on a single field of the object, it will run on any change to the object:

const fields = {

clicks: 0,

name: ''

};

// runs on every "clicks" change

$: console.log(fields.name);

<button on:click={() => fields.clicks++}>

clicks: {fields.clicks}

</button>

<input bind:value={fields.name} />If we only want the $-block to run on actual name change, we can achieve that by extracting name to a separate reactive variable. This variable will have its own "change event", independent of other object fields. In our example it's better to just define the fields as separate variables from the start, but in general this can be done using a $-variable:

const fields = {

clicks: 0,

name: ''

};

// uses primitive comparison under the hood:

$: name = fields.name

// runs on "name" change only

$: console.log(name);

<button on:click={() => fields.clicks++}>

clicks: {fields.clicks}

</button>

<input bind:value={fields.name} />Note that object-to-object mapping does not optimize anything and just runs on every dependency change. This is because the "pure" optimization is only applied when all dependencies are primitive (computation is not triggered), or the output is primitive (further dependencies are not triggered).

$-variables are an illusion

If you've spent some time moving $-variables around, you know they behave weirdly from JS scoping perspective:

- You can reference the "scope" variables (declared with let / const) declared after the $-expression (in normal JS, this is TDZ)

- You can access $-variable anywhere in the script, but the value outside $-blocks is

undefined

Here's an example to illustrate this behavior:

// you can reference variables before they're declared

$: name = state.name;

let state = {

name: ''

};

// logs "undefined"

console.log(name);The trick is, again, simple — $-variables are just sugar over a simple let declaration and an $-block that assigns to the variable. The variable declaration is hoisted to the top (which is funny, because this perfectly emulates a var declaration), and $-blocks become callbacks defined after the synchronous initialization code. The un-sugared equivalent of the code above will be:

// hoisted let declaration

let name;

// init block

let state = {

name: ''

};

console.log(name);

// $-blocks

$: {

name = state.name;

}If you want to go one level down, the output in both cases is:

let name;

let state = { name: '' };

console.log(name);

$$self.$$.update = () => {

if ($$self.$$.dirty & /*state*/ 1) {

// you can reference variables before they're declared

$: name = state.name;

}

};One funny side effect of this is that you can assign to the $-variable from e.g. another $-block, or a callback. The variable is not strongly bound to its definition, the last assignment wins. This would be quite confusing, though, and I recommend against such trickery.

To summarize, here's the result of my research:

- Svelte object state is truly mutable. "Reactive variables" are just regular JS variables with change event bus attached as a sidecar.

- Updates are only triggered by assigning to reactive variables — assignment is compiled to

$$invalidate(var_index, value)call. - Reactive block dependencies are determined at compile-time based on variables used inside the block.

- "Pure" optimization only applies to primitive values.

- Variable is the smallest unit of reactivity — changing a single object field triggers all the blocks using this object.

- $-variables are compiled to a hoisted let declaration and a callback called after the setup code.

Hope you've learnt something useful today — I sure have. Next time, we'll dissect svelte stores — follow me on twitter to stay updated!